The Effort Exertion Error: More Effortful Saving Leads to Less Investing

Update: This work eventually turned into a published paper here. You can download it directly here.

The Idea

After meticulously saving money during my first job after college (primarily by being a daily Mint.com user), I ignored my better judgment and chose mostly conservative investment choices for my savings. This of course turned out to be a major error, as the equity market has boomed over the last decade. As a graduate student studying human psychology and consumer behavior, I knew that the best course of action going forward was not to dwell on the past - I should learn from my mistakes and just focus on the future. But whats the fun in that? Given that I had decent resources to run scientific studies on human responses to risk, I chose to instead justify my past behavior by finding empirical support for it in the general population.

So why was I conservative with my investment choices? I believe it was because I focused on how effortful it had been to accumulate savings. I had lived in the heart of high-cost Washington D.C., and saving money had required constant vigilence towards my spending, careful budgeting and expense categorizing, and a heavy dose of self-control. Because I had put forth so much effort, I believe that I grew to value my savings above and beyond what they were actually worth. Similar to the IKEA Effect where psychologists showed that people placed more value on objects that they constructed, I too found myself enamored with my savings as a thing that I didn’t want to risk losing, and lost sight of its real value - as a medium to earn more money! My aversion to losing them became heightened from the effort I had exerted, and I made investment decisions for them accordingly.

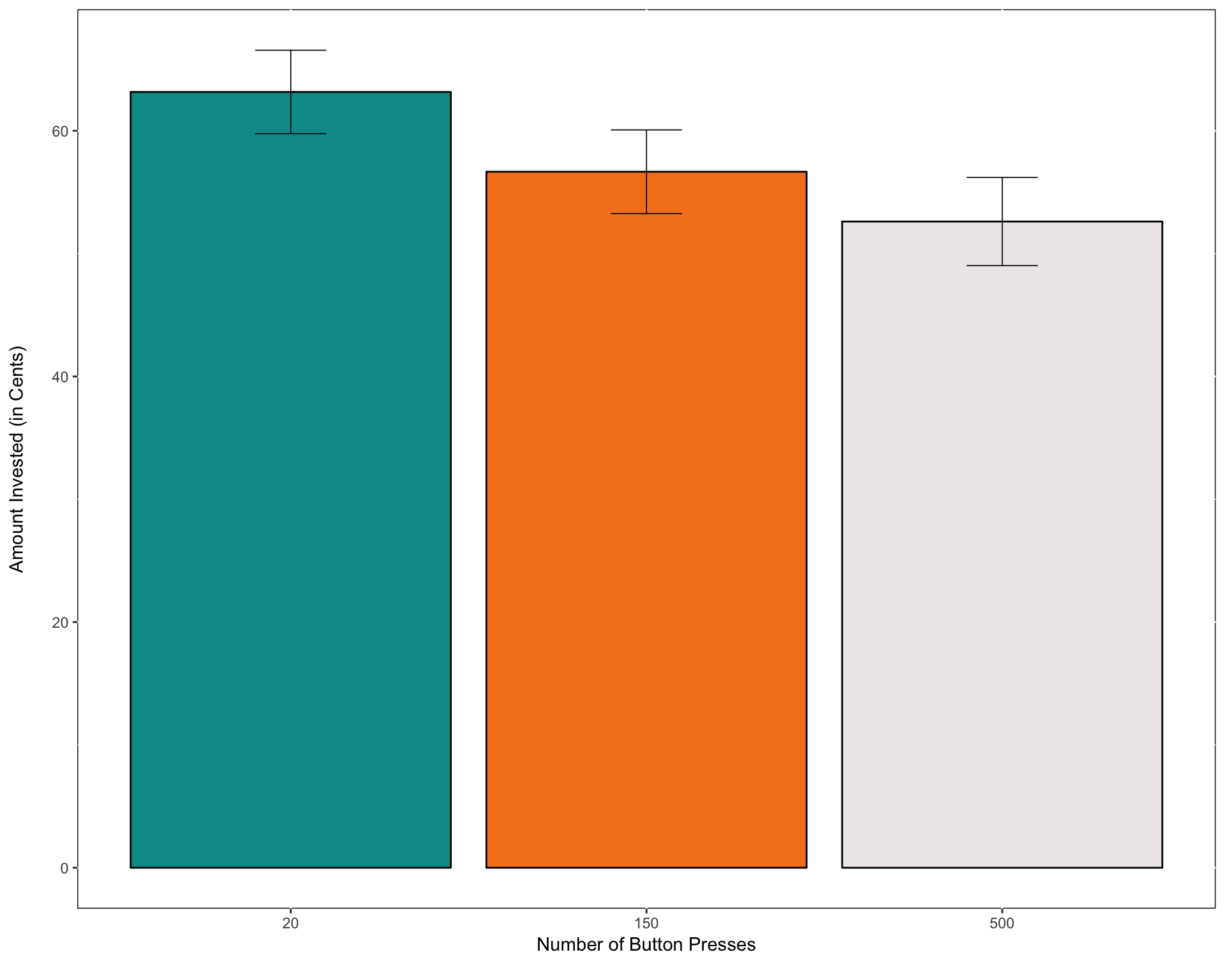

My research focused on this simple question - does exerting more effort to accumulate savings lower one’s willingness to invest those savings?